Utopian Movements in the United States and Berlin, Germany: The Architecture of Countercultures

The concept of the Law of Polarity applies to human society and culture as well, with everything having an opposite. Countercultures emerge as rejections of mainstream norms, representing the values and aspirations of a specific population during a particular period.

As new ways of living are explored, the corresponding architecture evolves to fulfill the utopian ideals of these new societies. Architecture is, therefore, a reflection of the culture it serves.

Architects play a vital role in shaping cultures, both reflecting and creating societal trends through buildings, cities, and systems that support novel ways of living. The avant-garde group Archigram was a pioneer in designing for utopian societies, pushing the boundaries of architecture’s impact on culture. Their works, such as The Walking City and Plug-in City, offer a glimpse of the limitless possibilities that communities can explore through design.

While Archigram’s designs remained theoretical, most counter-cultural movements worldwide influenced the surrounding built environment directly or indirectly. Buildings and public spaces provided a physical and intellectual space for countercultures to expand, usually following political unrest. Communities found a sense of belonging by organizing themselves within the city, as in the case of Berlin, or in rural communes, as in the United States. In both scenarios, the built and unbuilt environment shaped culture.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in the mid-1990s brought about political changes, societal tensions, and a desire for community and liberation. Planned development in Berlin decreased, leaving behind derelict land and abandoned buildings that created a breeding ground for counterculture. Underutilized spaces were temporarily repurposed to house communal programs like open-air bars, galleries, flea markets, gardens, music clubs, and sports facilities. Low rents attracted younger populations, fueling the city’s growth and its counterculture.

Berlin: Art and Music Counterculture

The post-industrial aesthetic of abandoned buildings reflects the rebellious counterculture born in Berlin. The architectural language of 1990s Berlin is characterized by a raw and sparse atmosphere created by steel and concrete structures, graffiti, exposed services, unpolished finishes, and makeshift furniture. The city’s temporary venues served as refuges for its people, solidifying the minimalistic and ascetic look and feel that continues to represent Berlin’s architecture and interior design.

In the United States during the 1960s, the “hippie” youth movement proliferated, marked by an ethos of harmony with nature, communal living, and artistic experimentation. The anti-establishment counterculture gained momentum with the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War. The era witnessed dynamic cultural forms of expression, from music and art to architecture and alternative lifestyles.

During this time, builders and planners gave form to the ideological shifts generated by the 1960s counterculture movement. The era was characterized by the rise of the back-to-land movement, turning away from activism and towards more ecological ways of life. Sustainability and minimal environmental impact fueled the movement, reflected in the architecture and utopian settlements that gradually emerged.

United States: The Hippie Movement

The 1960s were an interesting time to live in the United States as the “hippie” youth movement proliferated. Marked by an ethos of harmony with nature, communal living, and artistic experimentation, the anti-establishment counterculture gained momentum with the civil rights movement in the United States and the intensification of the Vietnam War. The era unfolded into dynamic cultural forms of expression, from music and art to architecture and alternative lifestyles.

During this time, builders and planners gave form to the ideological shifts generated by the 1960s counterculture movement. The era was characterized by the rise of the back-to-land movement, turning away from activism and towards more ecological ways of life. Sustainability and minimal environmental impact were concepts that fueled the movement and were reflected in the architecture and utopian settlements that gradually cropped up.

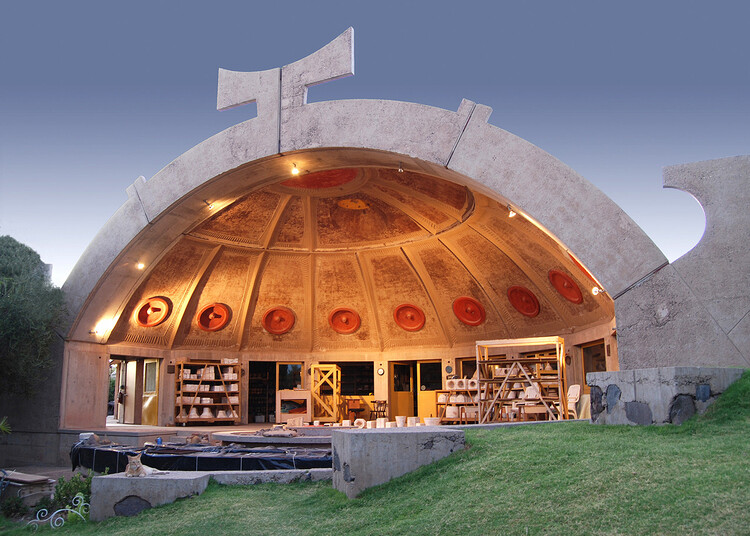

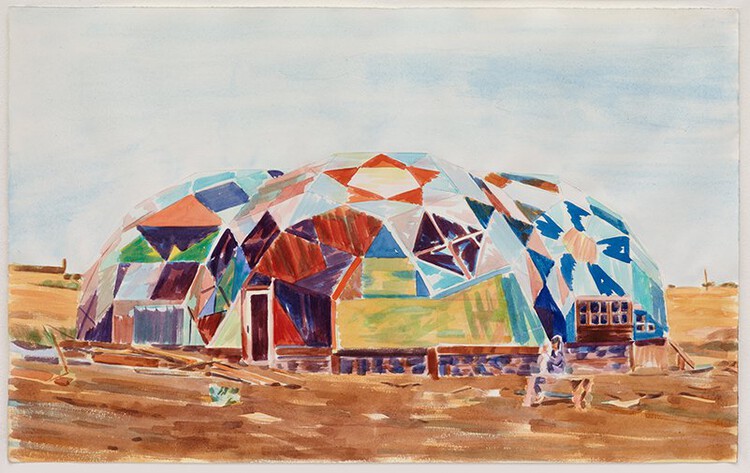

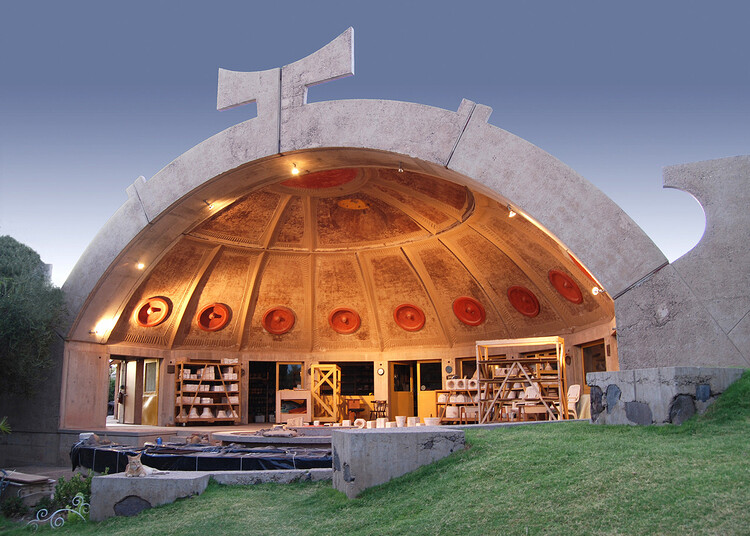

Drop City, a communal living project located in central USA, showcased the ecological, humanitarian, and speculative ideals of the hippie movement. The rural commune was a scaled-down version of Buckminster Fuller’s architectural concepts. The self-made zonohedron domes, constructed from scavenged materials, housed the artists’ community and were a fusion of avant-garde art and environmentalism. These geodesic domes were the first to be used for domestic living, as opposed to exhibitions and industrial purposes. Drop City was initially conceived as a prototype that could be replicated in other communes. Although the project had a short life, it influenced numerous experimental architecture projects, including Steve Baer’s Zome designs.

The radical designs of the American counterculture were symbolic representations of resistance against the technocratic ways of the past. Architecture was used to embody these philosophies by adopting forms such as inflatables, geodesic domes, and vernacular construction rooted in an environmental context. The use of glass, wood, and steel in limited quantities was instrumental in ensuring material efficiency within structurally stable domes.

The cases of Berlin and the US both highlight the importance of temporality. Countercultures thrive on experimentation and freedom, and temporal spaces and structures allow for changing philosophies and growing movements. As with any culture, counter-movements can manifest as built forms, which in turn support the larger cause. Architecture can be used as a tool to question contemporary lifestyles and physically shape futures that are more inclusive, sustainable, and equitable.