Sunlight and Concrete Converge at Tadao Ando’s Pub

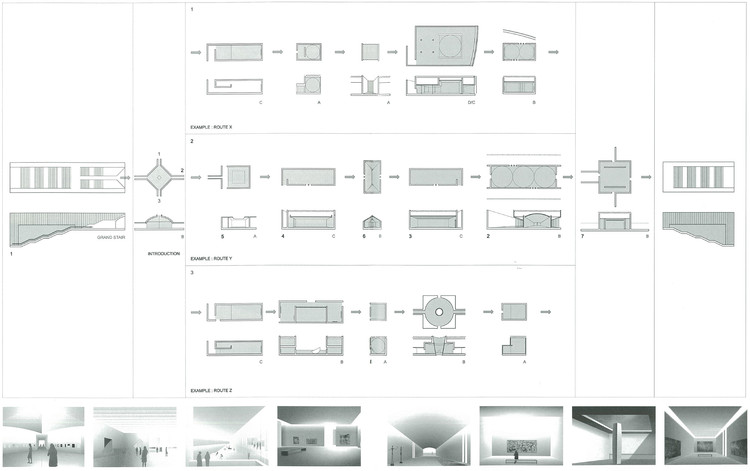

According to Tadao Ando, a Pritzker-winning architect, the consistent factor in his work is his pursuit of light. Ando’s architecture uses light in a complex choreography that is most fascinating when viewed as a sensitive transition.

The walls in his buildings sometimes wait calmly for the right moment to reveal striking shadow patterns, while other times water reflections animate unobtrusively solid surfaces. His fusion of traditional Japanese architecture with modernist vocabulary has greatly contributed to critical regionalism. While he is concerned with individual solutions that respect local sites and contexts, Ando’s famous buildings – such as the Church of the Light, Koshino House, or the Water Temple – link the notion of regional identity with a modern imagining of space, material, and light.

Ando’s masterly imagination culminates in planning spatial sequences of light and dark, as he envisioned for the Fondation d’Art Contemporain François Pinault in Paris. His visit to Rome, where he experienced the Pantheon, had a profound influence on him and confirmed his decision to continue his career as an architect. In Japan, the tradition of appreciating shadow and subtlety had defined the gentle sensibility of his home country. The Pantheon’s harsh beam moving along the dome and floor was completely foreign to him. However, the idea of introducing a more dramatic atmosphere influenced numerous projects from museums to temples.

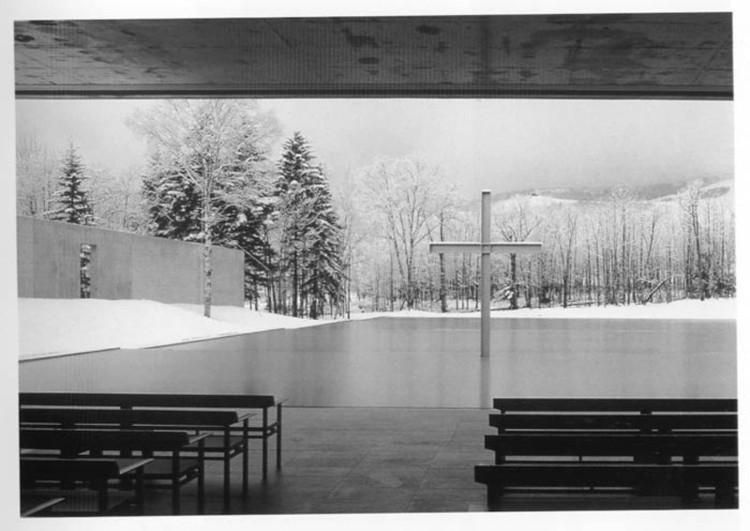

The renowned Church of the Light in Ibaraki, Osaka (1989) manifests Ando’s desire to confront light and shadow in a strong way, which is uncommon for traditional Japanese architecture. He achieves this with cross-shaped slots at the back wall of the sanctuary. Originally, Ando would have preferred to leave the glass out of the opening, which would have intensified the link to the Pantheon. But climatic conditions in winter made this unacceptable to the church.

In 2017, the Pantheon’s striking image reappeared at the Makomanai Takino Cemetery in Sapporo, specifically at the Hill of the Buddha. The Oculus, as one approaches the rotunda, transforms into a remarkable halo surrounding the Buddha’s head, exhibiting Ando’s skillful composition of brightness levels, space, and vistas. The Buddha is encircled by the blue sky and is elevated beyond the massive white statue. Ando’s use of cool, grey concrete for walls, ceilings, and floors creates a powerful homogeneity that sets his architecture apart from the bright white cubes of modern Western architecture.

Ando’s elegant slits between wall and ceiling generate a poetic rhythm of light throughout the day, separating vertical from horizontal and intensifying spatial depth by acting as channels for diffuse daylight. The moment of crescendo is brief yet intense when the rays of sunlight run parallel to the wall, casting striking shadows. The Koshino House in Ashiya (1984) features this effect in two variations: first along straight walls, then along an extension with a curved wall. The diagonal bands of shadow cut the fields of light, heightening the dramatic daylight gesture. The Vitra Conference Pavilion also benefits from a similar atmosphere with its straight and curved walls, where distinct shadows make the passage of time tangible.

At the Church on the Water, the cross in the window overcomes the distance between the congregation and the cross on the water. Depending on the orientation, the cross traces the course of the sun with a shadow pattern moving quietly across the floor – also staged, for instance, for the tower at the 4×4 House in Kobe (2003). An exception to the cross theme in windows occurs in Ando’s projects in the US where Mies van der Rohe’s influence seems to become perceptible. The House in Chicago, the Penthouse in Manhattan from 1996, and the 152 Elizabeth apartment block in New York (2017) display windows as a glass membrane with thin vertical lines. Hence, parallel lines of shadow become visible on the floor.

At the Church on the Water, the cross in the window brings the congregation and the cross on the water closer together. Depending on the orientation, the cross traces the course of the sun, casting a shadow pattern that moves quietly across the floor – a technique also utilized in the tower at the 4×4 House in Kobe (2003). In Ando’s projects in the United States, such as the House in Chicago, the Penthouse in Manhattan (1996), and the 152 Elizabeth apartment block in New York (2017), windows take on a glass membrane appearance with thin vertical lines, a style influenced by Mies van der Rohe.

The concept of surrounding buildings with reflecting pools has become an essential design element for Ando, adding animation to his work. For example, the rectangular pool at the Komyoji Temple in Saijo (2000) and the Modern Art Museum in Fort Worth (2002) enhance the building’s lightness, while the Langen Foundation in Neuss, Germany (2004), creates an impressive entrance gesture. At night, when the wall washed concrete behind the glass facade allows the buildings to glow from within, they appear to float on the reflecting pond. During the daytime, visitors can enjoy dynamic water reflections on the underside of the three prominent cantilevered roofs in Fort Worth.

The Water Temple on Awaji Island perfectly materializes the choreography of light. The journey begins with a void between a straight and curved wall in smooth concrete, with an open sky above. A texture of white gravel calmly lies on the ground with a new shadow pattern, creating the first bright scene. The journey continues to the round lotus pond, where an intriguing play of water reflections mirrors the sky with gentle waves. The rectangular entrance slit guides the eye downwards to darkness. The straight concrete walls reveal faint blue reflections from the sky before one enters the realm of diffuse red light. Vermilion wooden screens on the lower level turn the harsh, cool blue daylight into a warm diffused glow.

Upon reaching the main altar, a significant alteration becomes apparent: the direction of light no longer comes from above but from the front, drawing believers to the light and the sanctuary. This sequence of spaces condenses a pilgrimage within one temple – a purifying passage of whiteness, descent into darkness followed by awakening with bright red, signifying life.