EU delays combustion-engine ban vote amid German objections

Although German automakers such as VW have invested heavily in EVs (pictured), Germany still believes combustion engines run on e-fuels should be allowed after a 2035 EU ban on conventional fossil-fuel engines.

The European Union delayed a key vote on an effective ban on combustion-engine cars after Germany unexpectedly voiced last-minute objections amid concerns about how the bloc’s green plans will affect industry.

EU and German officials are in talks over how to reach a compromise over allowing the use of e-fuels in new cars after 2035, and there were signs from Berlin that a deal can still be reached that would allow the phase-out to go ahead.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is set to meet German Chancellor Olaf Scholz on the sidelines of a German cabinet meeting on Sunday, when the topic will likely be discussed.

“It is contradictory when the EU Commission calls for high climate protection targets on the one hand, but on the other hand makes it more difficult to achieve these targets through overambitious regulation,” German Transport Minister Volker Wissing told lawmakers Friday in the lower house of parliament in Berlin, adding that it’s up to the EU’s executive arm to come up with a viable solution.

EU ministers were scheduled to vote Tuesday in what was supposed to be a routine approval of a deal the bloc clinched last year to effectively ban new vehicles that run on fossil fuels beginning in 2035.

But Daniel Holmberg, a spokesman for Sweden, which holds the EU’s rotating presidency, confirmed the vote delay on Twitter and said diplomats will return to the issue “in due time.”

The delay reflects concern that Germany would have abstained — a move that could derail the bloc’s green plans, according to people familiar with the matter.

Some German officials have signaled that they think a deal is achievable that will preserve the broader ban.

“If the commission has a credible stance in conversations with the ministers and the German government, I’m optimistic that a solution will be found,” Sven Giegold, state secretary at Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, said Thursday, adding that the negotiations are difficult.

BLOOMBERG

Germany is seeking assurances that the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, will put forward provisions on how so-called e-fuels can be used in combustion engine cars after the 2035 cut-off.

While the bloc’s executive branch is obliged to come up with a proposal after consulting with stakeholders, there is no set timeline for such a move, beyond a general review in 2026.

The last-minute hiccup is highly unusual in EU lawmaking, given the deal between the EU’s 27 member states and parliament was struck in October last year and the upcoming vote is usually a formality.

The EU is scrambling to come up with a solution that would assuage Germany, meaning a compromise is still likely, even if the final approval is delayed.

The problem is that designing a carve-out for e-fuels, which are produced from renewable electricity, is likely to be technical, and there is not much time to reach a deal before EU parliamentary elections next year.

It’s unclear exactly what assurances Germany is currently seeking.

Germany’s objections were announced on Tuesday evening by Wissing. His pro-business party, the FDP, want a more flexible approach to some elements of Europe’s environmental program than other partners in the governing coalition. The FDP, which has suffered a series of setbacks in regional elections, is keen to be seen as a champion of technological choice as well as supporting German jobs.

For his part, Scholz sees synthetic fuels for cars as inefficient and is convinced that battery-driven e-cars will eventually prevail and dominate the market for consumer mobility, a person familiar with the matter said.

His reasoning is that they are projected to be much cheaper in daily operating costs than cars driven on synthetic fuel, which require a lot of power in the production process, the person added.

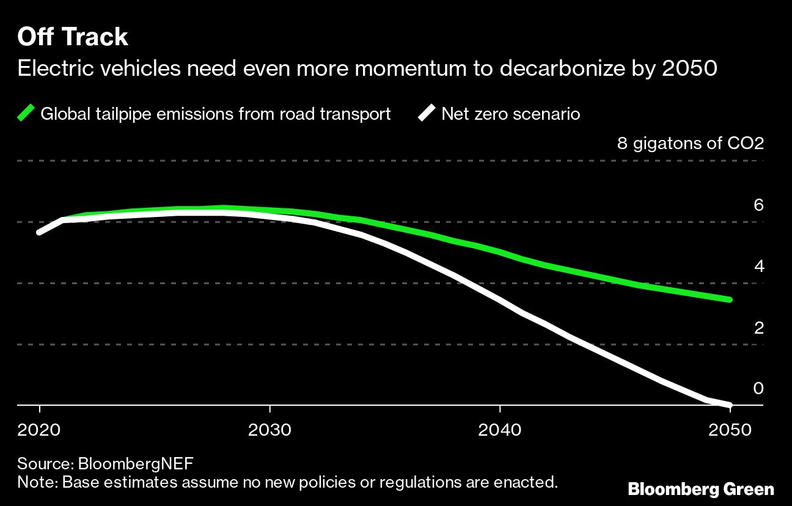

Decarbonizing transport is seen as a key pillar of the bloc’s goals to cut emissions by 55 percent this decade on the way to climate neutrality by 2050, but there are concerns over the impact on the bloc’s dominant auto industry.

The worries over the transition to electric vehicles was made clear last month when Ford said it will cut about 3,800 jobs across Europe, with workers in Germany and the UK set to be the hardest hit.

Many doubt that e-fuels are the solution, given they are significantly more expensive than conventional fuel, and currently very scarce. They also argue that such fuels should be used in aviation, which is more difficult to decarbonize.

Wissing also said Friday that the bloc’s plan to impose so-called Euro-7 fuel standards by 2025 — a move to reduce nitrous oxides and other emissions — should be re-examined as well.

“That is why it’s clear to me that we have to take another fundamental look at Euro-7,” he said. “The outcome must not jeopardize jobs, nor must mobility become a luxury good.”